- Home

- Jenny Bowen

Wish You Happy Forever Page 6

Wish You Happy Forever Read online

Page 6

Before the bad publicity of The Dying Rooms and the Human Rights Watch report, those southern orphanages were fairly easygoing and accessible. “The mountains are high and the emperor is far away,” as the saying goes. But, as the subject of both the film and the report, those orphanages had paid dearly. They were still feeling the sting when I showed up with my bright idea.

So despite the fact that they had been ordered by the ministry to allow our visit, orphanages in the south were not about to be stung again. The banquets were as lavish and frequent as in that first town, but caution was most definitely in the air.

Here was the routine: When we arrived at the gate, the “normal” children and staff were all outside, applauding. Everyone was dressed up and adorable. Cute little girls with lipsticked smiles brought us flowers.

First stop was the scale-model-of-our-future-orphanage exhibition. Usually that was in a giant glass box in the lobby. “Everything that we see today will be torn down soon,” they said. Although they definitely did look the worse for wear, most of the buildings were no more than five years old. (Mrs. Zhang told me that China is the land of instant antiques.) We spent more time looking at the models than visiting the children.

Then there would be the standard reception room visit, with fruit and speeches.

Finally, we’d make a quick pass through the children’s rooms. All was clean and orderly. The children were perfectly washed and combed. No less-than-perfectly-formed child specimens were on display. A brand-new toy had been placed in front of every child. It sat untouched, a foreign object. Most of the children had been given sweet treats to keep them in line. There were few caregivers present, though, and nothing could disguise the blank faces of the children.

A couple of the little ones escaped from their assigned chairs and clung to my legs, demanding to be picked up. The ayis grabbed them away with a nervous, apologetic laugh. The babies were snug in their cribs, each with a bottle propped at her mouth. When I picked up a bottle that had rolled away from a newborn too small to grab for it, it was quickly snatched up by someone and popped back into the tiny mouth. All shipshape.

Sometimes there’d be a little performance in our honor. We sat in little chairs. Wee tots wearing paper bunny ears sang a song about pulling carrots. The slightly older kids offered a Vegas-esque fashion show to a disco beat. The staff might treat us to a song or two. We applauded with great enthusiasm.

It was a year or more before I was able to walk into an orphanage in the south on a first visit without encountering some version of an orphan’s Potemkin village.

The one exception to the carefully staged but warm southern welcome was in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong Province, and Maya’s first home. The week before, while we were visiting two orphanages in southern Jiangsu Province, the Chinese government had begun a ferocious crackdown on the Falun Gong, a fast-growing sect of seemingly ordinary middle-aged citizens who engaged in qigong-like exercises and meditation and who had lately been staging public demonstrations, some drawing tens of thousands of followers. The government declared that the evil cult’s founder was pursuing a hidden political agenda. Police in several cities detained the group’s leaders. Thousands started gathering to protest the arrests—most visibly, in Beijing.

While we were in the air, flying south to Guangzhou, there’d been an emergency meeting, and by the time we landed, the government had announced a nationwide ban on Falun Gong on the grounds that it engaged in superstition and disrupted public order, thereby damaging social stability.

So instead of an escort to the orphanage, a phone call was waiting for us. All government workers, including those at the institutions, would be engaged in reeducation meetings. There would be no visits allowed that day.

WE WERE ORDERED instead to spend the sweltering day at the Bird Park on White Cloud Mountain. Wen went off to visit some Guangzhou cousins (she appeared to have cousins in every town in China), and I had an opportunity to begin to get to know Mrs. Zhang.

“I really feel very positive about your plan,” she told me. “I can tell from the questions you ask that you are sincere. When you are talking, I am feeling there is a light in the darkness.”

“What great good fortune that we found you!” I said.

“I should tell you,” she said, “that I am an orphan myself. Both my parents died when I was young. My aunt raised me and my sister. People often said my aunt should send us to an orphanage, but she would not. So you see, I know how sad that is to not have a mother and father.”

“Oh, Mrs. Zhang—”

“Foreign friends usually call me Joan. Zhang Zhirong is a difficult name. Not only that, do you know it’s a name for a man? When I went to college, I found they’d assigned me to the boys’ dormitory!”

The screenwriter in me knew she wasn’t a Joan. I tried it for a while, but eventually I just called her ZZ. It stuck.

“Do you remember when Herb called and you first heard about Half the Sky?” I asked her. “What did you think? That I was just some crazy foreigner?”

“Not at all,” she said. “The timing is good. China is just starting to open up. It may be possible. When later I speak to you on the telephone, I know for sure.”

“Why?”

“I can feel you are sincere. This is something different than the others. Not just sending money. You know, I’ve been doing foreign affairs for years. I talk to you and I know you don’t want to invade us or make trouble for China. You just want to make friends and help the children.”

“So what did you do after that first call?”

“I discuss with Miao. I tell her I can feel the seriousness. And I know the situation about the conditions in the orphanages.”

“You knew?”

“CPWF works with Family Planning Commission. A great number of babies are abandoned in these times. Besides, I work at UN International Women’s Conference in 1995. Foreign Affairs Office prepares us. They tell us about The Dying Rooms movie. They say women coming to Beijing from all over the world will criticize us. Be prepared, they tell us. Not everybody says China is good.”

“But you weren’t nervous about me?”

“No! I want to do this. I took a very active part. We are very close to Vice Minister Wan at Family Planning. He has friend, Madame Jiang, at Family Planning, formerly of Ministry of Civil Affairs. Madame Jiang has good guanxi with Civil Affairs Welfare Department Director General Yan. Short man, very nice. I personally bring letter to Director Yan explaining the purpose. He is expecting me. It’s kind of a friendly talk.”

“You made it happen.”

“The Dying Rooms is a bad situation. We say bad things always have a good side. This is a turning point. China wants to turn the page, but gradually. At the same time, they need help from outside. Of course, you have to have a friend or you can do nothing. Still, it is sensitive. When I take you on tour of orphanages, I must not say anything wrong. Not say too much straightforward with officials. Not too much detail because I don’t want to give them any chance to say no.”

As long as they don’t say no . . .

This I understood.

And I was smitten. What good fortune to find this woman, this ZZ! I adored and trusted her already. She would become my best friend, my big sister. My better half in China.

With ZZ beside me, I felt new confidence when we arrived at Maya’s orphanage the next day.

THE RECEPTION WAS anything but warm.

I’d been surprised when ZZ told me that Guangzhou was on the approved list of sites. I hadn’t even considered trying to launch Half the Sky there. Sure, the children were in dire need of help; Maya was proof positive. But from the little I’d been able to learn, Guangzhou seemed too big, too secretive, and too troubled. Despite Norman’s glowing report on that first telephone call—“best orphanage in China”—I’d learned from media reports and rumors that weak babies had a slim chance of surviving, let alone thriving, in that orphanage.

One thing was certain—this

little dream of mine had to succeed and quickly. We had to begin with conditions where success was at least imaginable. That eliminated Guangzhou. But I was in no position to argue.

“I’m so pleased to meet you,” I said to the closed face of Guangzhou Director Zheng, a compact fellow whose pocket protector held a single pen. Despite his controlled demeanor, a forelock of hair refused to stay in place and his shirt kept coming untucked. I concentrated on good thoughts: I was really trying to like him. “I was here two years ago to adopt my daughter.”

He grunted and frowned even further if that was possible. “No pictures,” he said.

He glanced down at the big bag of toy musical instruments we’d purchased the day before—“the Chinese way,” according to ZZ.

“And you can’t bring those toys inside,” he added.

He led us into what appeared to be a spanking-new showroom. The walls were lined with photo blow-ups of the children with various celebrity officials and assorted highlights of orphanage life.

One display featured three medals that had been won by older children competing in the Paralympics. “It would be great if the kids could hang those medals in their rooms,” I said. Then wished I hadn’t. Director Zheng appeared to be considering whether he should have me arrested.

Instead, he whisked us through a lightning-quick tour of one floor of one building in the massive complex. It was spartan but clean, and the many dozens of children looked physically healthy. That was all the opinion there was time for. Then we were outside. He couldn’t get rid of us fast enough.

“So Director Zheng,” I said as he ushered us out, “might you be interested in hosting some programs that are designed to provide nurturing care for orphaned children?”

I think he may have physically shuddered, insulted that we thought perhaps his institution might be improved upon.

“There are procedures that must be followed,” Director Zheng said.

And so we said our thanks and goodbyes.

SOUTH OF GUANGZHOU, near Hong Kong, Shenzhen was our final destination. It was, in those days, a long drive from Guangzhou through miles of lychee and banana groves dotted with new high-rise apartment buildings and construction cranes.

ZZ told me that this was the richest farmland in the nation. Soon it will be gone, I thought, just as the apricot orchards of my childhood had become Silicon Valley. Make way for New China.

We stopped at the border crossing to the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) and secured an entry permit for ZZ, required for Chinese nationals only. A dozen or so years earlier, before Deng Xiaoping’s policy of “reform and opening” established it as China’s first SEZ, Shenzhen had been a poor fishing village. Now the government feared that, without entry restrictions, all of China would move there.

No wonder. Shenzhen was another Hong Kong but, in that uniquely mainland way, flashier and tackier. Tucked between brand-new skyscrapers were budget hotels, job boards, streetside barbers, and vendors hawking junky bright clothes, cheap bus tickets, phone cards, and snacks. Factories of every kind encircled the city. And nobody was from Shenzhen. The place, at least in 1999, was overwhelmed by a steady stream of young migrant workers from every rural corner of China, making their way from farm to factory to take care of their families back home. They were China’s “floating population.” “You are a Shenzhener once you come here,” the saying went.

THE ORPHANAGE HAD a swank mirrored front. The Shenzhen director, a tiny spark plug in spike heels, was savvy enough to take advantage of the place’s relatively upscale location and open a public kindergarten for the community. The tuition she collected helped support the institution, with the added benefit of potentially (in my mind anyway) allowing orphaned children to mix with those from town. There was nothing special about the care in Shenzhen, but this setup, along with an unusually large population of about six hundred children—maybe something to do with all those young migrant workers—made it look promising for a pilot program. Furthermore, the Shenzhen director seemed open to new ideas and promised she could blast through any potential government obstacles. She guaranteed absolute, 100 percent cooperation.

Perfect! We had our first pilot site. I was elated. We wouldn’t exactly be saving the world on our first outing, but if the goal was to have a successful first year so that we’d be free to expand to more challenging areas, Shenzhen was definitely the place.

We still needed a second pilot site—someplace a little smaller, but with a large enough group of children to demonstrate positive impact. I asked Wen to return to Jiangsu Province, on China’s more sophisticated (and hopefully more open-minded) east coast, while I returned to California to tackle the practical side of developing the dream.

Chapter 4

To Move a Mountain, Begin with Small Stones

No one had said no, but they hadn’t really said yes, either.

No matter; I returned home without the slightest doubt that Half the Sky was on its way. I reported back to the board, and they were maybe a little surprised, but definitely pleased and excited, when I told them that we were actually going to do this thing!

A week later, Wen called to report that she’d found the ideal spot in Jiangsu Province for our second pilot site—Changzhou, a small city not far from Shanghai. There were about 120 children, which would make it a midsize orphanage. As in the majority of places we’d visited, the children’s basic needs were taken care of, but that was it. Wen sent photos. When I saw the barren rooms and blank faces of the children, I agreed: Changzhou would be pilot site number two.

Now we began to make detailed plans. Wen started reaching out to her connections in China to identify a pool of young teachers for the preschools, and I set to work on a plan for the babies. Beyond adopting Malaguzzi’s inspiration about children and caregivers learning together, I hadn’t made much progress in thinking through how the infant nurture program would work. When I suggested to the orphanage directors during our recent visits that the residents of the adjacent senior housing could come over daily and cuddle the babies, out came the old China Smile. Fixed grin, eyes glazed over—no way was that idea going to fly.

So now I created an early childhood advisory group online. I invited adoptive parents who were child development professionals to help us plan our approach. Our first two volunteer nanny trainers were selected from that very committed pool. Even better, I met Janice Cotton, an early childhood professor, researcher, and practitioner who, although not available for this first outing, would not only design our infant nurture program, but one day oversee the development of an elegant and comprehensive child development curriculum for Half the Sky.

I informed the board that there would be a few other things to figure out quickly, before we returned to China. I explained that, on my trip, when I’d begun to see a few too many of those China Smiles, I may have made a few impromptu and rather bold promises:

“We will not only transform the children. We will turn orphanage rooms into playrooms of the highest international standards! We’ll fill them with colorful and sturdy developmentally appropriate toys!”

It hadn’t taken long to get the message that many of our potential Chinese partners (especially the men) were really into enhancing their real estate holdings. They wanted the shiny toys and plaques and other assorted symbols of success. So, of course, I obliged. Now we had to figure out how to deliver.

Lucky for us, we had talent in the house. Our good pals on the board, Daniel and Terri, were experienced designers. Daniel had been a cabinetmaker before becoming a screenwriter and professor; he’d even designed and built play equipment for the children’s ward of a hospital. Terri was a painter with a gorgeous sense of color. They designed the play equipment, furniture, and color scheme that we still use in our children’s centers today. And, best of all, they volunteered to lead our builds.

Paying for this grand plan would be tricky. We’d already tapped out friends and family. Not a single one of the very promising foundations I’d researched was w

illing to even look at a proposal. We had big ideas but had accomplished nothing yet, and Chinese orphans were not high on any funder’s priority list—actually not on the list at all. Ours was not considered a pressing global issue.

Still, we launched our first public fundraising effort with great optimism. We collected names and addresses of anyone we thought might want to help the children. I wrote an appeal letter. Rob Reiner, a colleague of one of our board members and an advocate for early childhood education, helped us with an insert stating his support. By New Year’s Day 2000, we were ready. We sent our first direct appeal off in the mail and held our collective breath:

On the July Fourth holiday last year, the first anniversary of our daughter Maya’s adoption, I watched her playing in the backyard, exuberant with friends and family. I marveled at this little being who had taken over my life and so fiercely captured my heart. And I was overwhelmed with gratitude for the gift of her life in mine.

I know you’ll understand when I tell you that my happiness that day was tinged with sorrow. I couldn’t get the image out of my mind—the image that haunts me still: the babies lying alone on their backs, the toddlers strapped to walkers . . . all those abandoned little girls in orphanages in China who will never know families. Who will never know Maya’s joy. . . .

Like many developing countries, China has extremely limited resources for its orphaned children. The main priority in welfare institutions is, and must be, food and health care. Everything else is an unaffordable luxury. Caretakers want to give the little ones more, but they are simply overwhelmed. So the children languish.

The lucky ones find families. For those who don’t, the future looks bleak. Chinese society is rooted in the family. Life for a girl-child in China is not easy. Life for a girl-child with no family is unspeakably tough. Education is their best hope . . . for most, their only hope. But many of these little girls will get no education.

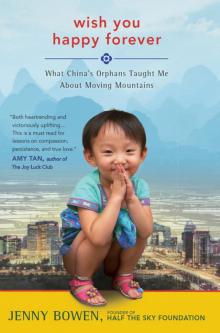

Wish You Happy Forever

Wish You Happy Forever